How About That? A Celebration of Black Queer Resilience with Rayceen Pendarvis

Full disclosure — you’re about to read an interview featuring a living legend and icon. While the term “legend” is used rather freely these days, this isn’t one of those occasions.

If you’ve seen Jennie Livingston's documentary Paris is Burning, or the award-winning series Pose, you might’ve heard of the House of Pendarvis. “Houses” are chosen families, led by “mothers” and “fathers” — providing guidance and support for their “children”; mostly gay, transgender and gender nonconforming people of color. Founded in Harlem in 1979, the House of Pendarvis served as a haven for dozens of queer people of color daring to live out loud and celebrate their identities.

Rayceen Pendarvis was the second “child” to join the House of Pendarvis upon its founding. Shortly after, she became an activist for social justice committed to making every space a safe space for LGBTQ people throughout the country.

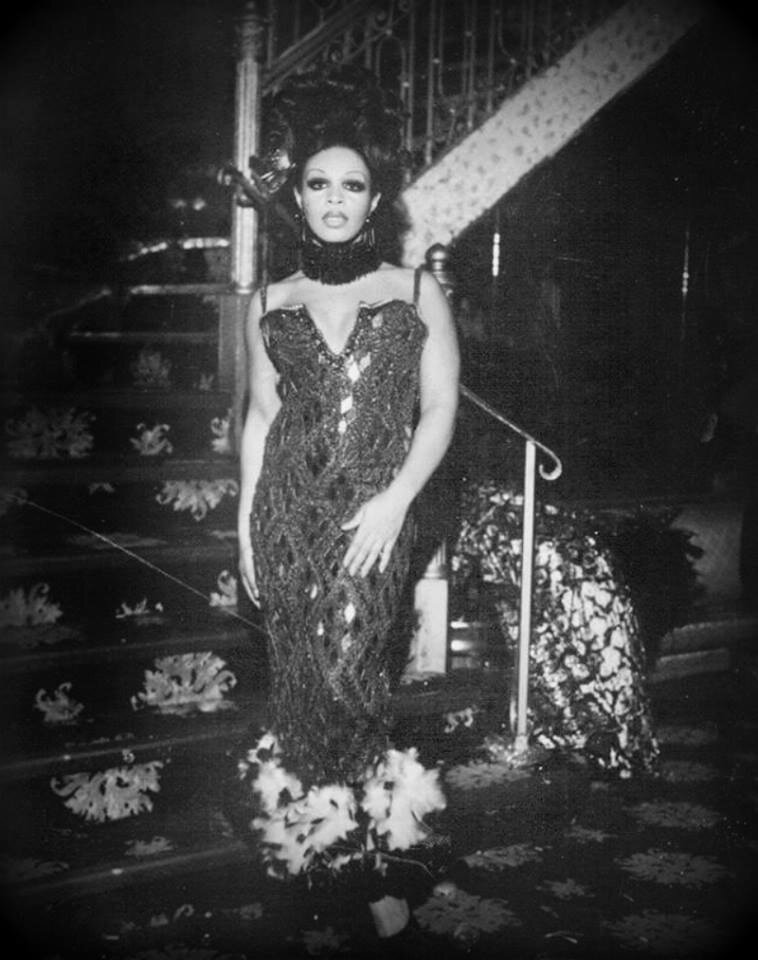

Pendarvis is an emcee, entertainer, activist, SWERV magazine columnist, former advisory neighborhood commissioner, and lifelong Washingtonian. Known as the, "High Priestess of Love," “Queen of the Shameless Plug, and Goddess of D.C,” Ms. Rayceen can be spotted about the city, slaying the masses wearing a signature headwrap, regal fashions and smize.

Days prior to our interview, I found myself wondering: What is Ms. Rayceen going share with a genderqueer, disabled, high-femme from Kansas? How will we see our experiences reflected in each other; and what in the world should I wear?

We sat down for dinner at my home on a brisk Tuesday night in Northeast Washington, D.C. I will forever cherish this conversation and hope everyone reading can see a bit of themselves reflected in the journey and experiences shared.

These are the lessons and learnings of, Ms. Rayceen Pendarvis.

interview CLIP:

Blessitt: I just have to say: You're a legend, a real one. The moment you agreed to an interview with me, I called all my friends and freaked out. I was like, can you believe Ms. Rayceen said “yes”?

Rayceen: Oh, I'm honored. I’m very humbled when people ask me to share my story or my experience on this journey. Sometimes you don’t see the sacrifice, or the dedication, or the work, or the commitment it takes to do what we do and live as our true authentic selves.

““Sometimes you don’t see the sacrifice, or the dedication, or the work, or the commitment it takes to do what we do and live as our true authentic selves.””

Blessitt: I mean, you are a child of the House of Pendarvis.

Rayceen: I am. Avis Pendarvis was my mother — she grew up here in Washington, D.C. with a lot of my cousins; they all went to high school together.

Avis was just someone I was drawn to. Her light was amazing. She was a woman who spoke 10 different languages. She was valedictorian of her class. Our spirits just connected, and people always say, "Oh, you remind me of Avis." In my lifetime I had two mothers: my mom and Avis, who were both instrumental to allowing the development of me.

My mother is my greatest champion. How blessed I am. My mother raised me and is still living at 91—I'm one of her caretakers. I am so honored that God has allowed me to take of her because she took care of me. She allowed me to be me and loves all of me. I don't know where I would be without her.

Blessitt: That is such a blessing.

Rayceen: It is. I came up with a lot of kids whose parents put them out if they were gay or transgender, but thankfully my mother would always open the door. She went through the journey of watching my friends transition in their sexual orientation and then watched many of them transition from birth to death. She went with me through the journey of AIDS and HIV. I taught her about it because she came from a generation where she didn't understand all that. We had the real conversation, “You don't catch it from sitting on toilets; you don't catch it from drinking water.” We talked about the things people feared. Of course, it was scary for her. It was scary for me, but what a journey it was to go through it together.

Blessitt: How do you think things have changed for our community since?

Rayceen: Coming up through an era when we were segregated … I was very young, so I didn't experience [Jim Crow racism] because our areas where always self-contained. Black communities took care of themselves. We had everything we needed. Through the women's movement, the civil rights movement and the gay movement, we all came together. People who were oppressed had to stand together. I've been to the March on Washington, the Capital Pride Parade, Black Pride—and felt so much unity in all those spaces.

I am a child of God first. I am a person of color, same-gender loving. All of that is a part of my experience. I cannot be one thing without the other. It is all inclusive of my being.

We stood together out of oppression. Once we arrived, some of us forgot. Some of us got comfortable in spaces of, “I've arrived, I'm OK now. I don't have to be around those people in those areas because I've now gotten out of oppression.” When people forget their struggle and other things occur to remind them they're Black or same-gender loving, when they get a smack in the face, when they get called out; then they realize: “Oh no, I got to join the movement again. I got to fight. I'd forgotten what it feels like to be oppressed.”

““I am a child of God first. I am a person of color, and same-gender loving. All of that is a part of my experience. I cannot be one thing without the other. It is all inclusive of my being.””

So here we are in 2019, in the climate created from the White House and the powers at be. There was a time they called us niggas face to face—now they cleverly call you a nigga or faggot or a sissy. It's written in programs, legislation or things you don’t realize. You don't have to see the sign, No Blacks, no Jews, no Gays, but you feel it when you find yourself wondering: “How come I didn't get this job or how come I didn’t get this apartment? Or how come I felt a certain way when I walked into this room?”

We have certain people that aren’t as free as we are. There are certain people who will hate that freedom—

“How dare you be?

How dare you exist?

How dare you be black?

How dare you be queer?

How dare you be spiritual?

How dare you be comfortable in who you are because I'm not free?

If I'm not free, I'm going to not allow you to be free.”

We deal with compartments of people who want to constantly oppress other people. We must use that experience as a teaching moment. How do you educate someone who hates you? If I argue with you, I get angry and then you get angry. Nothing gets accomplished. If I'm calm in my spirit and in my demeanor, if I love those who don't love me, I will see change. Free people, free people. So, we got to free people and meet them where they are. We're all part of humanity. You don’t have to like me, but you got to respect me.

The U.S. Supreme Court upheld the ban on transgenders in the military. Another slap in the face. We get comfortable. Gays can get married. In some cities, you have IDs that, if it does not match your birth and you have proper representation, you can check female, [or X in four states]. But everybody’s not free everywhere. So today in 2019, we still must fight for basic human rights. When one person is oppressed, everybody is oppressed. The fight ain’t over, sweetie. When people are free, we rise together.

Blessitt: Many would say the civil rights movement brought equality and pride to the Black community, but long before it, we were proud to be Black.

Rayceen: We were beautiful and Black. I remember a time you walked down the street hearing, “What’s up sista? What's up brotha?” It was a time when it was OK to be Black. The phrase “I'm Black and I'm proud” was all over the radio, music, poetry and movies—celebrating our experience as Black people.

Then there was a time it was gone. Now I can see there are things on the rise. I feel good about films like Moonlight and Beale Street, that tell the black queer experience. Black people aren’t going anywhere—we’ve always been here. It’s not enough to be on television—we must own it: own our production, own our rights and tell our own stories.

All these amazing authors and writers—Omar, Tyree, Sister Souljah, Toni Morrison, Bebe, Zane. All those stories are part of the Black experience, including the Black queer experience. Queer folks have been in a midst. There’s always been a colorful gay uncle or a butch aunt who lived with her “roommate.” Aunt Pat and Teresa have lived together for 40 damn years. It's always been in the family. Sometimes they didn't talk about it, but they didn't have to talk about it. They knew it, they felt it, and sometimes they were celebrated and accepted in the family. But they fought to be respected. Tyrone couldn't come home with his boyfriend Jamal, but they knew that Tyrone was gay, and his “friend” was Jamal. And he would not come home unless he would be affirmed and allowed bring Jamal. So, he had to slowly come in and educate his parents about loving Jamal—that if you're going to love me, know that Jamal is in my life, and you got to love me and him together.

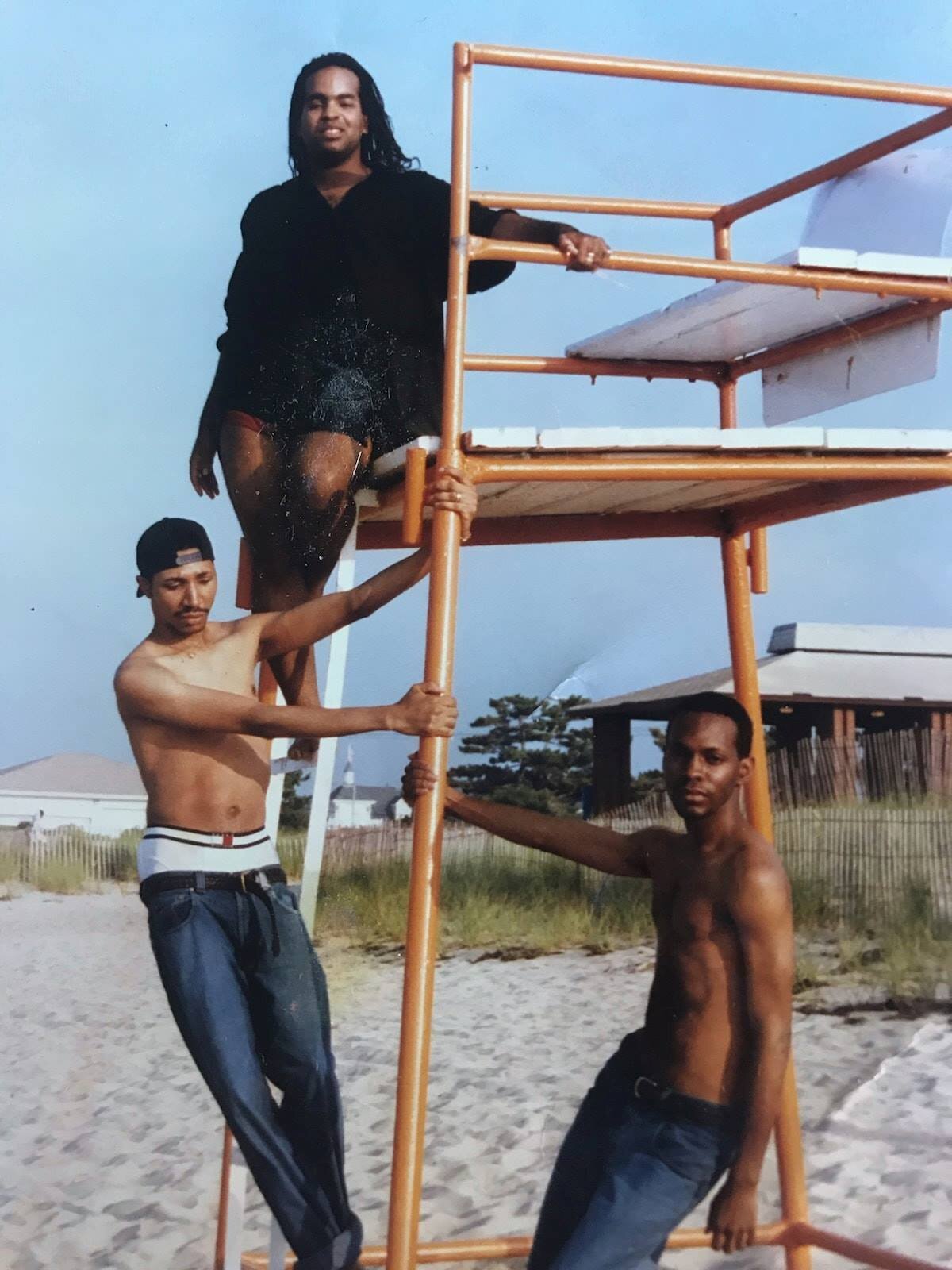

When I was coming up as a young, queer, black person in Washington, D.C., life was segregated. We had pockets to travel and move as queer people. We stayed in the village in New York City, on Castro in San Francisco, and at Market Street in Philadelphia. In D.C., we had Dupont Circle, we had downtown, but we clustered together and came together as queer people out of safety. There was safety in numbers. We were like gay gangs. That's how some of the houses formed, you know, because some of the kids would get kicked out and they would be loved and accepted in other places. So as much as folks try to destruct the ball community, it was very similar to sororities and fraternities. And houses in 2019—where the kids are voguing in Russia and Paris and Milan and Tokyo—to see that makes me feel good. That Avis and Paris and Dorian and Peppa are looking down smiling because they had to break down doors; they had to create a society and a subculture in the midst of oppression.

We were being celebrated when the world wouldn't accept us being transgender or openly gay in the 1940’s, 50’s or, 60’s, but we had to create pockets within the Black community where we could celebrate our queerness. So, if we were not being treated as the queens we were, we could at least be a queen for a night. People shun that thought, but we had to create to celebrate. I mean, look at the Harlem Renaissance era of all these those amazing people: Audre Lorde, James Baldwin, Richard Wright, and all of these people who created and celebrated within the queer Black experience. We walked hand in hand through the storm to get to this point.

Blessitt: Many would say the black experience and the Black queer experience are not connected nor should they be.

Rayceen: I'm so grateful growing up here in Washington, D.C., because there was so many affirming spaces and queer people that when I came out, I could be celebrated in spaces and with people that cared enough about me to nurture me. The transgender community — warrior women and men — they were amazing. They worked in a time when people couldn’t comprehend how could you be all of this? This amazing, seven-foot transgender woman, in a world where people just weren't going to celebrate you. But they were able to maneuver in the Black community; they created stuff. They weren't given a girls’ job, the girls made jobs: after-hours joints, running numbers, selling dinners, gambling and all of that. They made things and created clubs and jobs for people. They would create beauty shops—the girls were in there: burning and cooking and pressing’ and curling, honey. Then they realized that if they could count money—add and subtract—then they could build a sustainable business.

But it wasn't always like that in every city; people were not as understanding in rural areas. When the great migration of people of color coming from the South came here, they were leaving places where they could not be free or explore the full potential of what it was like to be Black in America — where they realized there was potential for them beyond sharecropping. So, you come to cities such as Washington, D.C., Philadelphia, Chicago and New York City where these amazing people were doing stuff— dancing, singing, medicine, all of it was a possibility.

One time a friend of mine said: "Oh, come over. My cousin is a jazz singer.” Child, I went over to see her and the woman playing the piano was Shirley Horn. Pearl Bailey grew up with my aunt. They all grew up in the same church where I grew up. Pearl Bailey was always Aunt Pearl to me, but little did I know she was The Pearl Bailey, this amazing film star who was a part of our history. And these people also saw a little something that you didn't see and had their ways of saying: “Honey, I see who you are. Fly, fly little bird—fly sparrow.” They would plant things in you when in their presence. They saw that Rayceen was going to be Rayceen. They affirmed, celebrated, protected and nurtured me.

As we grew into who we were, we would go downtown and hang out. We knew as young people there was a certain part of you could not go over. We knew that colorism and racism existed when I was very young. But I never experienced it to the point that my parents or my grandparents had. God bless them for shielding us.

Blessitt: So, how did you come out?

Rayceen: Oh, my coming out? Was I ever in, honey? That's the question.

I think that we grapple, and we have points in our life where we were scared to really be who we are.

I always tell people I'm a father of five and a mother of many. Having children or other extensions of my children early on in my life was a blessing. It saved me because I realized there were more things in life that I had to do. I feel like I was always who I was, even when I fought it. Fought it for a long time. Because you know, people tell you when you're coming up: “Oh child, you were always who you are. You always had your little hand on your hip and you always had a little switch in your dip.” So, I don’t think I didn't know what it was. I just didn't have a name for it. I just was me, you know?

There was an older gentleman, Miss Billy Matthews; that's what we used to call this little queen. When I was 13, she had to be maybe about 18 or 19. This queen was unapologetically queer. Miss Billy wore her little hip huggers in booty shorts and clogs. She was very glamorous —very Bohemian and chic and fab. And she had a body for the gods. In the summer, she would wear these little booty shorts and a fabulous little fringe bag. She had a little top tied ever so gently—giving a little midriff. She would give it to you, honey.

I would call her out. I would look at Miss Billy and call her every kind of sissy in the world, every kind of queen and read her, “Oh, look at that sissy. Here comes Miss Billy Matthews … here comes that old sissy.” I'd call her out, but she would never, never read. She’d just go about her business. She'd keep twirling. Holding her head up high. Little did I know, I was calling her all the names with my hand on my hip!

I feared that someone was going to call me out. So, if I called her out quicker, nobody would be paying attention to me. Many years later at the very first Black gay pride, which I am honored to say I was the very first host—standing on that stage, I looked out in a sea of close to 40,000 Black, same-gender loving people, and I saw Miss Billy Matthews. When she walked over to me after the show, I knew exactly who she was—still looking fabulous. Older, but still looking fabulous. She said: "I always knew. I was waiting for you to find out who you were gonna be." I hugged her and apologized and thanked her because I was very cruel to her. Years later, I would see her again and she was frailer—it was the early stages of HIV and AIDS. She would always hug me, and I would always have kind words for her. She would always say to me: “I'm so glad to see the gauntlet has been passed. You are running an incredible race.” She let me know I had work to do. I honor her and all of those who nurtured me along the way, who are not here today. I carry their memories in everything I do. That's why my activism is on 100 percent of the time. I cannot dishonor their memory by not doing the work.

So, I always knew who I was because even as much as I fought it, once I understood the power and gift of being Black, queer and me, and celebrating that light in me — I never had to darken it for anybody else. So, to get to that point. It took work. It took me to talk to myself and love myself and say, “OK, Rayceen. It's all right. Let your nails grow long. Let your hair grow and let twirl. Celebrate yourself.”

Love you, and then love you as you age. It's OK to be a little thicker, a little fuller. I embrace my gray and getting older and being queer, but still being fabulous. Do not apologize for being yourself. You don’t need to darken your light so others can shine. Learn how to flame off and flame on for safety. It’s important. You can be a queen but understand everybody ain't gonna want you to wear your crown. So, it's OK to allow yourself to put that crown in your pocketbook and be a queen without being loud. You don't have to be boisterous, but you can be proud and respectful. We had to be boisterous and loud because we had to tell society we were here, we had to matter, we had to show the world we had to fight through so much. We had to constantly let people know we were here, and we were not going to be erased. People would advise me: “Don't tell anybody you’re gay, girl. You can't be gay all the time.” But once you break the chains, you don't want to have anybody put you in a prison again. There's a lot of kids that couldn't be who they were and chose to check out. Whether they physically checked out or emotionally checked out—numbing themselves with drugs, sex and alcohol. You must affirm yourself and affirm your space.

Once I decided who I was, I told everybody. I went to high school at McKinley Tech. I came into ninth grade with a girlfriend. Senior year, I had a boyfriend and I accepted who I was. The summer of my ninth-grade year, I discovered that Rayceen was Rayceen. I learned to fully celebrate me. I had wonderful friends who nurtured me. I wasn't going to go back once that closet door was kicked open, baby. I could not and would not. I understood the power and importance of what it was to be Black and queer.

I accepted who I was and put people in my space that affirmed me. You must create your tribe; create your community; create people that affirm you daily; that you celebrate them; that you want to be around. Back then, we were around with everybody, butch queens, transgenders, performers—drag queens who were boys on Tuesdays and on the weekends, they were girls. We created a tribe.

I learned from these people—Tina Teasley, Pat, Gracious, Tracy, Puffy, Mimi, Miss Roberta, Miss Erlene, Miss Linda, Avis—all these amazing people on my journey. I took their strength. I would look at these amazing people and say, “God, how can you walk through the world?”

The first time I came out, there was a woman named Joanne—she was transgender. Joanne had to be close to seven feet—standing. She was not the most beautiful thing. She was hard on the eyes, honey. But she maneuvered through this world as a woman because she knew she was a woman. She acted like a woman. She carried herself like a woman. She spoke as a woman. Every essence of her being was a woman. You would question it for a second, but once you were in her presence, you wouldn't ever question her again. When I first met her, she was going through nursing school. She ended up becoming an amazing nurse at a hospital. When she would walk into the room, people would look at her; she would open her mouth and you’d move on. The presence of her spirit took over. She was dark, with blond hair, and she wasn't gonna go back to anything else but her blond hair. I remember one time going to see a friend of mine's father at a university hospital. He said: “My, the nurse that comes in, her name is Joanne, she's very strong. She picks me up. She doesn't need any help. She just moves me and does what she needs to do. She's the nicest lady in the world. She's the sweetest woman. She takes care of me like no other.” Not once did he ever say, “I think she's a man.” Not once. That's how she carried herself. She was respected in the medical profession—revered. It was amazing to see people like her.

Blessitt: Did you ever feel unsafe in public back then?

No. For one, I could fight and I could read. I was clever; it got me out a lot of things. I would meet men and they'd call me all kind of faggots and sissies and all that. But because I was quick on my feet and I can read very cleverly, I’d say, “Well, why are you worried about a bunch of damn sissies anyway? You ought to be giving us some goddamn money. Give me $20, because that's less pussy for you anyway.” Then they would stop in their tracks and burst out laughing. So, I learned to disarm hate with humor. I learned quickly that if somebody came at me, I had to have a clever read that made them think.

But there were moments when the police didn't always like us. When I think about how the police would harass the gays. I was very young, and we'd be sneaking out the back door headed to the after-hours joints where we mixed with everybody from politicians to prostitutes to transsexuals and drag queens. We just wanted to be there, but there were still sodomy laws on the books. In D.C., you could be arrested if you did not have an article of male clothing on you. If you looked like something that you were not, they would call it masquerading—that was the law. So, I would hang with all these transsexuals and they look like women, but they always had on boxers or they wore men's socks or men's garters because they could be harassed. The police would come and pull us over or they would come to the clubs and harass the girls. Because I was young and cute and could grow a beautiful ponytail, I looked like the cutest little girl and they never bothered me. But they harassed them, and they would do anything to humiliate them. But we fought against that. It was people of color. We rallied. We’d say, “Y'all can't keep coming down to the gay clubs and the gay neighborhoods and harassing us.” We collectively reached out early on and talked to other people in our community. Some were religious, some were activists long before the word was deemed activism. We stood together as people of color because when you start harassing the gays who were Black, that meant you was harassing the Black folks. So, if you are harassing all of us and we all are catching hell, we got to stand together. Back then when hanging out, you had a gay club on the corner and a few doors over on their block would be the straight club. Gays and straight folks all hung together, all on one corridor because it was the areas where the people of color went. Then we had our Latin girls that always came, and we met with the little Latin children. Then we went uptown and hung out with the white queens—we all traveled together. We knew that we had to collectively pull together. I had to find people that loved me, I had to find communities that loved me. Thank God, we found each other.

I guess there was a point that I did fight who I was. I don't like checking boxes. I can't stand it. You know, this new community where people ask: “What are your pronouns? How do you identify?” I'm a human being first. I'm a human. You cut us, we all bleed.

““Once I understood the power and gift of being Black, queer and me, and celebrating that light in me — I never had to darken it for anybody else.””

The people who oppress us and hate us aren’t going to say: “All the trans, get in one corner; all the butch queens get in one corner; all of them lesbians get in one corner.” When they come to get the LGBTQI community, they’re coming to get us all. They won’t have time to check your box: “Nope. We don’t like any of you.” So, we must learn the importance of loving us first. It isn’t always about these labels now. I get it. Folks fought a long time to come and be free and say: “This is who I am. I identify with the T and the Q and the I.” But how many letters do we have to add before we really love us—completely and fully? We need to learn to love ourselves. I don't need a letter to affirm that I'm a same-gender loving person; that I know that I liked boys. I knew that a long time ago. I don't need a letter to tell me that—I'm free. Having a letter doesn't make me free. My spirit makes me free.

Blessitt: You found your tribe at a young age, became a child of this legendary house, then you started the chapter here in D.C.?

Rayceen: The chapter was always started. God rest her soul, Linda Pendarvis, who is no longer with me—my oldest sister. She was Avis' first daughter and the first child in the House of Pendarvis.

I like to say I am elder of the House of Pendarvis, or, now that they call us "icons" and “legends.” I can fully embrace that because I've been around, I've survived, I've seen, I’ve struggled, and I fought. I have all the right to call myself a legend or an icon.

I think about why God kept me to share what it was like coming through this journey to get to here. How do you go on when you look around and all your peers are gone? I remember surviving the AIDS epidemic ... after 2,500 people you love die, you stop counting. All those people that I met on my journey along this way made me who I am. I took a little piece of their strength, their endurance, their freedom and listened to their stories, wiped their tears and listened to their fears. We were all scared together. It could have been me but—through the grace of God—it wasn’t.

I have seen the March on Washington, the March for the King holiday, the Capitol Pride March, the Black Pride March, the Youth Pride March, the Trans Pride March, the Latino Pride March, and now the Silver Pride march. To see those things in my lifetime, makes me understand the importance of why we fight and refuse to be erased as Black queer people.

I really love the strength of your generation. Sometimes you got to just do it — just jump out there and say: “I'm going to put on my cape today with my Ugg boots, my fur coat and my Chanel glasses, and I'm putting lip gloss on with a full beard and march. And I’m not worried about what people are going to think. And I’m not thinking of you all, if you're going to do is stare at me.” The bravery it takes these young people to say, “This isn’t 1948, this isn’t 1998, this is 2019 and I'm a twirl bitch” inspires me. But sometimes they look at everything as if it was given to them. Somebody had the fight so you can be free. In their mindset, to be in 2019 and 15 years old and coming out and saying: “I'm to be part of the queer community.” Now, they can get online and can connect with other people and see there are folks like them—they can see a tribe. It's on television, good or bad images—we’re there.

There was a time when we weren't. When we'd been cleverly talked about in beautiful lines and Tennessee Williams plays and books and cleverly written. Then we came through Essex Hemphill's experiences and their stories and tongues tied. Then we were talked about, and we were written about through these clever poems of Audre Lorde. They required you to sit down and read them and understand that she wasn't just talking about being black, she was talking about being black and being a woman who loves another woman. That was all part of her journey; it required you to think and process and read in these clever lines they’d written. Today's generation doesn't get it because everything is there. They could click on the TV and see the wonderful, fabulous Miss Lawrence who I love dearly. People like her, who through vehicles such as Star, she is no longer one-dimensional. She's this full deep part of being black and queer and gender nonconforming, and she has been given a platform to showcase that. Because as queer people, we need a little visibility. We need Miss Lawrence. I get that everybody can't be queer, and everybody doesn't have the strength to come out the closet. Let's be clear, there are a lot of queer folks in our community that don't identify but write the checks. They stand in the rooms and in the meetings, making sure our characters are well-represented.

We need our allies. We need the people such as Sheryl Lee Ralph, who lift us up to help tell our stories and say we must be in the room. The Jenifer Lewises of the world, Whoopi Goldberg, Ryan Murphy, a white gay man, who has the power to help our stories be told. Pose is so important because it tells our story and employed 250 trans people—first time ever being done in the history of film and television. That's why I created the Ask Rayceen Show7. Iit showcases a LGBT artists, poets, writers, singers, painters, dancers, politicians, families, spiritual leaders, folks who are not spiritual. Atheists are on the same stage with bishops—all coming together with LGBTQ people of color and telling our stories. That fuels me and pushes me and connects with Reel Affirmations to have films tell our stories, to partner with them and to be a host for that. Sometimes we disconnect people of color from the LGBTQ community, but with me, you get all of me. I'm a mother, I'm a father, I'm a son, I'm a daughter, I'm a child of God. I'm over 50. I'm gender nonconforming. I'm a two-spirit and I'm free.

Bishop [Yvette Y.] Flunder told me: “The moment you decide to stand up and be an activist in this community as an LGBTQI person of color, you wear a bullseye on your back. So be prepared for the arrows to come. Sometimes they will come from your own people, which hurts the most. But when you are changing lives and making a difference and walking unapologetically as your true self, you are doing what was called of you.” When she said that to me, I had tears in my eyes. Sometimes you don't feel like what you're doing is worth it all. But moments like this, sitting here with Blessitt Shawn during black history month, being interviewed by a person who is unapologetically queer to tell my story, to tell what it's like to be, to encapsulate all those things together.

How honored I am.

How blessed I am.

How humbled I am.

Blessitt: I love you.

Rayceen: I love you too. This has been amazing. I want everyone who reads this to live your truth, walk in your light, celebrate your freedom, and never let anyone make you feel less than.

How about that?

- Shirley Horn was a very popular award winning jazz vocalist and pianist during the mid to late twentieth century born and raised in Washington D.C.

- Pearl Bailey was a very popular actress and vocalist during the early to late twentieth century, based in Harlem and Washington D.C.

- "Calling out" is the act of sharing someone’s personal/private affairs and/or identity publicly without their consent; often done in a derogatory manner.

- Originating in African-American and Latinx gay and transgender spaces, "read" refers to the act of subjective truth-telling usually regarding something unflattering; this is most frequently done publicly, without the consent of the recipient.

- Voguing is as style of dance born in the late 80's ball scene that imitates the poses struck by a model on a catwalk.

- The "Ask Rayceen Show" is a D.C.-based event series showcasing live-entertainment and DMV-based businesses/organizations, artists and community members held the first Wednesday of every month.

Share this article

Qwear is an independent platform that empowers LGBTQIA+ individuals to explore their personal style as a pathway to greater self-confidence and self-expression.

We’re able to do this work thanks to support from our amazing community. If you love what we do, please consider joining us on Patreon!

Support Us on Patreon