On the Intersection of Being Jewish and Trans

Hearing the words “Israel” and “transgender” on the news over and over is like hearing my own name called when I least expect it. It’s odd and unsettling. I’m at the crossfire of two wars I never started and no matter how many times I flip the switch, it just won’t turn off.

As a trans Jew, my body is a battleground. My identities are weaponized to achieve evil political goals. When these battles collide, they expose the deep sickness embedded in our society. Through dissecting these collisions, we can understand how systems of oppression work and slowly deconstruct their entanglement, knot by knot.

The term “intersectionality,” coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw in 1989, illuminated how when people exist with multiple marginalized identities, their experiences intersect and overlap in ways that create an experience “greater than the sum” of its parts.

The conservative attempt to separate the plight of religion, race, ability, and queerness aims to keep marginalized communities apart. The key to fighting these systems of oppression is for us all to come together and unite in our fight for equal rights. The ban on teaching critical race theory, which includes intersectionality, aims to prevent us from understanding and therefore speaking out and fighting back at the systems that oppress us.

Whenever we are silenced, we must speak louder, lifting up one another’s stories, and telling our own. With all the news centered around my identities, I felt compelled to document how my transness and Jewishness intersect to expose my observation of our depraved society.

Who is Santa Claus?

My brother and I at the piano

I was born August 27th, 1988, raised just outside Boston, and attended a reform temple which described themselves as “a warm, inclusive Reform Jewish community.” Growing up, it was a place of joyful singing, learning, and “tikun olam,” or social justice. My early memories of the temple are of running around with other kids, singing songs, feeling the warmth of Shabbat, and eating delicious challah.

Posing in a floral a yarmelka, age 4

When I entered Kindergarten I discovered that the vast majority of friends and classmates observed a different religion that I knew nothing about in which magical characters visited their homes. Who is Santa Claus and the Easter Bunny? I was totally out of the loop.

My family, particularly on my mom’s side, was adamant that we cannot assimilate to American culture, as that would mean embracing the Christian customs which shaped it. One day after Kindergarten I ran up to my mom when school got out and proudly held up my coloring activity, showcasing what I believed was a very cute reindeer. She grabbed it out of my hand and scolded me. That reindeer in the drawing is known as Rudolf the Red nosed Reindeer and is not to be colored in again.

Being banned from participating in these activities at school didn’t strengthen my connection to Jewish traditions, but it did stunt my social development. How can you socialize with people when you don’t understand what they are talking about and you’re not allowed to participate in their customs?

Come first grade, I befriended the child of a full-blown Christmas fanatic. Their house looked like a Christmas Tree Shop had vomitted in every room. When I saw it, I’m sure my jaw was on the floor. I’d never seen so much Christmas paraphernalia in one house and haven’t seen anything like it since. My friend’s older brother was surprised by my reaction and spread a rumor that I was afraid of Christmas trees. His neighborhood gang took to chanting, “Christmas tree! Christmas tree!” every time I passed them. Their taunts escalated into a daily round of ding-dong ditch at my house, providing an unsettling reminder that we didn’t belong.

You think I’m a what?

Just as I didn’t know there were religions outside of Judaism for the first few years of my life, I also didn’t know that everyone thought I was a different gender and sexuality than my own. I was expected to identify as female and be attracted to men, whereas my identity lay closer to male and my attractions were mostly towards women and femme presenting people, with my interest in men only becoming apparent post-transition.

From the moment I became self-aware, my gender felt as clear and obvious to me as the the fact that the sky is blue and gravity will keep us on the earth. I enjoyed a short bowl cut and wearing my brothers’ hand-me-downs. I assumed my brother and I were the same. Early on, I figured out that I would some day grow up and be expected to live as a woman. When asked what I wanted to be when I grew up in pre-school, I couldn’t picture myself performing any career, or even existing, as a woman. When it was my turn to accounce what I wanted to be, I paused, and then said I wanted to be a boy. They told me that was impossible. Everyone else in the class was allowed to be whatever they wanted, no matter how impractical. My heart sank in that moment.

I had my first crush on a girl in first grade. I was filled with embarrassment and shame. I could barely look at her when I walked by her. I didn’t understand why I felt so ashamed, as I didn’t even know what a crush was, but I knew others would think it was wrong and sick.

Being gay wasn’t exactly considered bad by my parents and their friends. In fact, my parents had a gay friend who we had visited the year before. But it certainly wasn’t acceptable for young children to identify as gay and coming out in elementary or middle school would have been social suicide. In the early 90’s there weren’t queer characters on TV that I could see. I don’t know that I would have even been able to stay in school if I came out because the bullying would have been too severe. I really came to hate myself due to all these overwhelming feelings I had towards girls. All my peers with my assigned gender seemed to enjoy their role in life and I didn’t know why society’s expectations tortured me but not them. And perhaps they were tortured too, but in different ways, and maybe later in their lives, but at the time, I only saw them looking comfortable and never questioning their roles. They could talk to pretty girls without blushing. They could wear dresses effortlessly. Meanwhile, I was tortured.

My queerness felt like a growing bubble of guilt and shame growing inside me until I was about to pop. Every night before going to bed, when it was just me and my thoughts, I used mental gymnastics to convince myself that I could live a straight, cis, life by trying to imagine scenarios in which I could be attracted to men in my current form. No wonder I developed insomnia.

Indoctrination

At Hebrew school, we learned about Jewish history, reading stories from the Torah, discussing their moral teachings, and we learned about Israel as our homeland.

We were taught about Israeli culture and life, ate Israeli food, and colored in maps of the regions. I barely knew Palestinians existed. When they were mentioned, they were only brought up as terrorists who were trying to destroy the Jewish people.

The words “Israel” and “Jewish” were inseparable. The concept of returning to Israel; both literally and figuratively, fill Jewish prayers and texts. “Jewish” meant “human” as I knew it. Being Jewish was everything to us. Without Judaism, we were nothing. Without Israel; we are nothing. There was no concept of life without Israel because Israel symbolized our freedom and self-determination as Jews. When you put it like that, it can be a difficult fantasy to let go of.

But that’s exactly what it is: a fantasy.

My ancestors fled Eastern Europe in the 1800’s to escape pogroms and widespread persecution. They narrowly escaped the WWII holocaust—the penultimate attack on our people after 2 thousand years of persecution, lowering the number of Jews in the world to just .2% of the population. The Holocaust imposed a very real threat to the future of the Jewish people and preservation of Jewish culture. Assimilation with other religions posed another threat as Ashkenazi Jews moved out of their tight-knit shetls communities and dispersed around the world, fleeing to whatever countries would accept them. There are certain phrases that I can still only say in Yiddish, the language of the shetl—a mix of Hebrew, German, Slavic, and other languages picked up in our travels. There’s simply no English word for “ballabutching”: someone who is speaking at length, in an overly dramatic way, without much substance or relevance. And why would there be? That’s just such a Jewish thing to do. These cultural things will always be a part of me whether I go to Temple or not.

In seventh grade at Hebrew school, we spent the first hour learning, in graphic detail, about the WWII Holocaust. They taught us every detail of how Jews were rounded up and shipped to concentration camps where they were torn apart from their families, tortured, raped, and murdered. They showed us Schindlers list and I still remember every horrifying detail. I had no safe place to store this information in my brain. To a twelve year old with a vivid imagination, hearing the stories made me feel like it was happening to me and my family.

Israel, founded in 1948 at the end of the war, was presented as the light at the end of the tunnel — the return to the promised land and the the birthplace of Judaism as we know it, where we would no longer be persecuted and we could live our lives in peace. “Never again,” they’d say. “Never again.” The concept of returning to our homeland in Palestine is known as Zionism. (Zion which refers to Jerusalem or, more broadly, the Land of Israel, as mentioned in the Hebrew Bible.)

After the Holocaust unit, we would spend the next hour conversing and studying with the Rabbi. It was a safe space where he asked us to think deeply about our Jewish identities and the meaning of life. It was also the first time I encountered a queer publication. He brought in copies of Bay Windows for us to read. His daughter was gay and he wanted to normalize it for us. In fact, he had left a conservative synagogue for ours in search of a more accepting place.

I had my bar mitzvah at age 13, which was called the feminine version at the time, but saying those words trigger me. I stood in front of all my friends and relatives, wearing a dress I hated, and read from the Torah. The photographer didn’t like the way I was standing so she made me pose in feminine stances. My grandfather got up and gave a speech about how the next big event in my life would be my wedding. I felt like my family was holding an event for an imaginary daughter and I wasn’t even really there.

A week after my bar mitzvah, a tragedy I’d never imagined struck. My beloved aunt Paige was murdered on September 11th. The news shattered me. I decided the world was inherently evil. If humans were capable of such cruelty, I couldn’t see the point in life. As I grew older, I realized I’d have to carve out meaning for myself.

I’m not gay

When my breasts began to grow, the nightmare intensified. I was confused, embarrassed, and horrified. I didn’t want anyone to see them. My body didn’t feel like my own. I thought something was wrong with me because I was supposed to like growing up, but I just hated every second of having those things, which I’d later only refer to as “tumors.”

My 8th grade English teacher gave everyone a journal where we could write about whatever we wanted. I wrote about Paige and my fear of losing another family member. My teacher read every students’ journal and wrote encouraging notes in the margins. She offered me such a safe space. I had an enormous crush on her and the shame I felt at age 6 came flooding back. I had my own journal at home that no one saw but me. Even so, I couldn’t look at the words, so I created a code. I decoded it when I got older and was shocked to see what I wrote: “I’m not gay I’m not gay I’m not gay.”

In ninth grade I went to a more accepting high school where “gay” wasn’t a dirty word. I was shocked to see gay students thriving and with bustling social lives. In health class, we watched a few episodes of Ellen, where her character came out as gay. She explained that no matter how hard she wished it away, it was part of who she was. Watching that, I felt something click inside me: my queerness wasn’t going away either.

Ellen Degeneres’ character Ellen accidentally announced over the airport speaker to her love interest that she’s gay in “the Puppy Episode” of the Ellen sitcom in 1997. I didn’t see the life-changing piece of television until 4 years later in 2001.

I came out to my mom in the car at age 14. I was too ashamed to look at her so I said it while we were both looking ahead at the road. I just wanted her to reassure me that it’s ok to be gay, that she would love me no matter what, and there was nothing wrong with me. Instead, she got flustered, took a wrong turn, and told me to wait until college to “experiment.” I went back into the closet for two more years. It was clear I’d be all on my own when I came out, and I needed to be prepared.

Clashing expectations of masculinity

Jewish religious and cultural traditions place a high value on learning and knowledge. Torah study is baked into Jewish life and is thought to bring you closer to God. It is a great mark of Jewish masculinity to have intellectual prowess. At the dinner table, all the boys and men would ritualistically debate topics like music or history while shutting out the women and people FAAB from participation. I believe this was how Jewish men expressed their masculinity. This was the Jewish equivalent of men gathering around to cheer for their favorite sports teams, while women cleaned up after them. These contrasting versions of masculinity—both domineering and boastful, yet expressed in different ways—left me feeling less masculine both because of my transness and Jewishness.

I never felt like a girl and more like a boy than anything else, but what really is masculinity? What makes a certain aspect of myself masculine? I never really had an answer to this question, because it’s all relative depending on culture and time period. It became more a question of how I feel most comfortable and how I want to be seen.

Today I identify as nonbinary, while the map I have of my body is one with traditional male anatomy. I do feel quite femme in my personality and flamboyance, but also masculine in my body, decisiveness, and abrasiveness. My feelings are delicate but my body language is brash. Perhaps I’d feel more masculine if I’d been raised in a household which valued things like sports and physical strength.

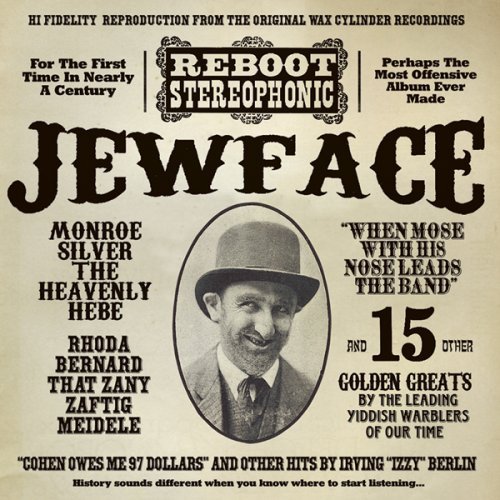

Picture the stereotypical "nerd" archetype: a socially awkward male, poorly dressed, can’t get a date, clumsy, and oblivious to social cues. He’s often portrayed as out of place, serving as a source of comic relief. Howard Wolowitz from the Big Bang Theory is a classic example. This nerd archetype is a direct descendant of Jewface: the use of exaggerated Jewish stereotypes in popular culture complete with prosthetic nose.

These depictions emasculate the Jewish character, depicting him as weak, physically incapable, and therefore unsuitable for traditional roles like protecting a family or procreating. This portrayal taps into longstanding stereotypes of Jewish men as intellectually sharp but physically inept, reinforcing the idea that they are unfit for the more rugged, macho roles of the Western or heroic archetypes.

“Jewface” Album covering antisemtic songs from the late 19th and early 20th centuries, featuring the face of a man with an obsurdly large prosthetic nose.

Instead of resisting or trying to escape the stereotype, many Jews found a sense of belonging in comedy and performance, with some of the most iconic comedians in history being Jewish. However, I believe the drive to make others laugh often stems from a deeper place of pain. A defining feature of Jewish humor is its self-deprecating nature, which reflects a complex relationship with identity, survival, and resilience in the face of adversity. Humor, in this context, becomes a way to reclaim power.

Sports were a core factor of male socialization for the outside world but wasn’t central to the standards of Jewish masculinity I was raised around. My family took no interest in sports and I struggled to integrate with the population without even a basic understanding of how sports games work. This created quite the contrast with all my Irish catholic classmates for whom hockey and baseball were practically religions of their own. As I recall, my brother and I were the only kids whose parents didn’t sign them up for soccer. In gym class our teacher told us to play soccer without explaining the rules because he assumed we all knew them. I didn’t even know what a goal was and I kicked the ball in the wrong direction. These things are so baked in American culture that we don’t even think about it, but how would a 7 year old know what a goal was if not explicitly explained? To me, this was just one of many humiliating moments when I felt like the odd one out.

I've noticed that Jewish men in the US are much more open about discussing their feelings and, in general, tend to be more expressive. The stoic, emotionless version of masculinity was never something I experienced in my close circles.

The archetype of a nerd is based off a Jewish charactacture and has become a staple in American pop culture. We are portrayed as socially inept, awkward, and obsessed with intellectual pursuits, often depicted as outsiders. When Jews first immigrated to the US, just as blackface and yellowface were the popular entertainments of white people of the time in Vaudeville, Jewface was used to portray us as charactures and Jewish actors were often forced into this stereotype. Ultimately, we had to embrace this stereotype and own it, as it was the only way to be accepted.

Over time, these exaggerated traits were transformed into the "nerd" archetype—a character who is both intellectually gifted and socially alienated, often marked by thick glasses, a penchant for technology, and a lack of physical prowess. Today, when nerdy characters are portrayed negatively, this stereotype is harmful to Jews, even when the character themselves is not Jewish, because of the Jewish undertones.

I am not an incubator

When I came out at age 16 I was forced to grow up overnight. All of a sudden, I was facing all these new problems: how to deal with homophobia, how to navigate my life, whom to come out to and who not to, which battles I fought and which I let be. But the most difficult situation to navigate was my mother, who took every opportunity she could to try to get me to date boys and stop being gay. That was when I realized she didn’t really love me—she loved the idea of me that she’d created in her head.

I had to advocate for myself in ways I never had before, making the decision that I wanted to live as authentically as I could with or without my family’s support. While I continued receiving room and board from my parents, they were hardly parents to me. They couldn’t help me with any of the problems I was facing as I learned how to navigate homophobia as a newly out teenager.

I then learned the true reason behind my mom’s aversion to my queerness: She had a plan for me to birth Jewish children and continue the family line. When I found out, I felt used, like all I was to her was an object — an incubator. It never occurred to her that I might have my own plans. While I wanted kids, the thought of carrying a child made me deeply uncomfortable. I hated having breasts so the thought of them growing bigger in pregnancy seemed like a nightmare. I felt like a disappointment. I tried to regain my parents’ love by becoming more involved in the temple to show them that I was dedicated to participating in and passing along our culture despite my queerness and transness.

The more I studied queerness and gender and talked to the queer friends I made in high school, the more I realized that the female identity was something thrust upon me but not who I am. But I didn’t exactly feel like a boy either. I learned of the word “genderfluid” and decided to try it on.

I came out to my mom as genderfluid during a heated argument over a shirt she deemed not feminine enough for me to buy. She screamed that I was a girl while my dad sat in silence. While I didn’t fear being thrown out, I knew she could make my life a living hell. Due to her seemingly sweet personality and meek build, no adults believed me that she was abusive. I had nowhere to turn but to go back in the closet and pretend to be a girl.

📷 Mira Steinzor

When I looked in the mirror, I didn’t recognize the person looking back at me.

I always felt ugly. I failed at conventional femininity. I stomped. I couldn’t keep my legs together. My face was covered in so many freckles they joined clusters together. My nose was stereotypically large, and my skin was pasty white. I looked nothing like the made-up Arian models in magazines.

When I saw myself in pictures and videos I saw an ugly Jewish man in drag with a nose too big for his face. I couldn’t separate my internalized transphobia from my internalized anti-Jewishness. All the negative stereotypes compounded into one thing. I just hated myself. Working through it is difficult because the two identities have blended together in a way where it’s hard to know where my root issues come from.

At 23, I found the strength to come out again—this time as trans and nonbinary. I cut my hair, replaced my wardrobe with men’s clothes, and shed every remnant of the identity forced upon me. I changed my name and pronouns and, at 26, underwent top surgery. I knew I needed it without a question when I realized that I envied every flat-chested character I saw in movies, no matter their circumstances. I’d rather be in jail with a flat chest than free with breasts, because freedom and femininity could never coexist for me.

My mom put up a fight at each stage of my transition process. She begged me to let her use my dead name and call me her daughter. When I had top surgery, she staged a protest by not coming to the hospital as she normally would with any other medical procedure. She also didn’t tell me or my dad that I was allergic to Percocet. I had a horrible allergic reaction, but luckily my partner Ru caught it in time and I didn’t go into anaphalaptic shock. My mom’s transphobia almost killed me.

After top surgery, I loved the way I looked for the first time in my life. But I still have flashbacks that ugliness I used to see at times. Sometimes when I don’t get a haircut in a while, I get reminded of having long hair and immediately return to the memory of feeling ugly. I don’t know that it ever completely goes away. It’s a common nightmare that I wake up and have long hair again, or I have to put on a dress.

My introduction to anti-zionism

Through the trans community, I found belonging—a family of thoughtful, creative, weird, and fiercely loyal individuals. They expanded my understanding of intersectionality, systemic oppression, and social justice. Our lives weren’t just about freeing trans people — they were about freeing everyone, starting with those most vulnerable. Our gods are the trans women of color who started the movement, who we owe our lives to: Marsha P Johnson, Sylvia Rivera. But they also challenged me in ways I wasn’t prepared for.

I was particularly startled by a photo of a highly respected trans activist at a rally holding a sign that read “Fuck Zionism.” This was my introduction to the idea of Zionism being a problem.

As trans people, we see the interconnectedness of our liberation and the liberation of other groups. Our interest in human rights naturally lends itself to causes like Palestine.

Palestine is a popular cause in the trans community in the US because of our government’s heavy involvement in the war, funded by our tax dollars. Being both trans and Jewish meant being pressured to understand the situation in Israel and form an opinion.

Mentioning I was Jewish on a date, my date pressed me on my views on Israel. I got the sense that if I gave the wrong answer she would lose my number. This was a lot of pressure because I’d never been to Israel and never really learned about the history of the ongoing war and now I was being tested. “I don’t really understand what’s going on,” I said. She looked really nervous and it was clear I needed to continue. “But I think what Israel is doing is really messed up.” She let out a big sigh. I passed her test.

In 2012, when Trayvon Martin was murdered, the Black Lives Matter movement awakened me to the systemic violence Black people face. My white skin had shielded me from the dangers and corruption of the police.

I posted about Black Lives Matter on Facebook and my Dad texted me “careful about BLM. They are members of the BDS movement.” Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions, is a nonviolent Palestinian-led movement opposing Israel’s occupation and human rights violations.

The same person who taught me about civil rights and read to me about Rosa Parks was now sending me anti Black Lives Matter texts. What the heck was going on, and why was a peaceful movement such a threat to him? Though he was a Zionist, I knew he didn’t agree with many of the actions of the Israeli government and I thought we could find some common ground.

I started reading. I read books recommended by my parents, like My Promised Land by Ari Shavit, a so-called “liberal Zionist.” But within a few pages Shavit’s dehumanization of Palestinians and obvious racism repulsed me. I turned to my queer friends for recommendations and subsequently underlined every other sentence in On Antisemitism, by Jewish Voice for Peace, which remains my favorite book on the subject. What I discovered horrified me: atrocities committed in my name, lies I’d been told my entire life, and the realization that Zionism wasn’t liberation—it was colonization.

I learned there are many forms of Zionism, and some exist more as theoretical ideals than as political realities. Early Zionists envisioned a Jewish state in our historic holy land, often framing it as a solution to centuries of anti-Semitic persecution. Some supporters argue that the concept of Zionism in its purest form—the dream of a safe haven for Jews—was not inherently problematic. They suggest that the idea only became contentious when it turned violent, as political Zionism took root and materialized into a state. However, this argument overlooks a fundamental truth: the establishment of a majority Jewish state in a land already populated by indigenous Palestinians was never a neutral or peaceful endeavor. I saw no issue with Jews moving to Palestine, but as refugees, not as colonists.

Coming out as anti-Zionist provoked angrier reactions from some family members than coming out as trans. My grandfather thought I was brainwashed by terrorists and antisemites. Logic and reason had no place. We couldn’t even lay the groundwork for a productive conversation. We had a completely different take of events that led to Israel’s founding, as well as current day events. Who struck whom first, who was a terrorist verses civilian. He had been fed lies his whole life and there was no way I could sway him. So while he sent his checks to Israel Defense Fund, I pored my heart into social justice work that directly fought his own efforts. We sat together in love and harmony despite opposing each other on the war.

At age 29, I redid my Bar Mitzvah, wearing a suit, as a form of healing. My grandfather helped me decide on my new Jewish name to use during the ceremony: Shalom (Hello, peace.) It suits me perfectly.

Now that I’m anti-Zionist, I feel out of place in most temples and Jewish spaces aside from groups that are explicitly pro Palestine like Jewish Voice for Peace. When I started working at MIT I got coffee with the school rabbi, but found that her connection to Israel and anger at my point of view wouldn’t conduce itself to a good foundation of worship.

My Jewish identity took a backseat until it was thrown in my face during a protest in 2024. Pro Palestinian students and staff blocked the hallway to my office, including many trans people I knew, demanding that MIT divest from any alliances supporting the war on Palestine. Then the Zionist students wrapped the Israeli flag around themselves and blasted Jewish prayers from their boombox to drown out the protestors. Prayers that I’d sung growing up to ground myself, with my congregation, were now being weaponized. It felt like my two core identities were fighting one another right there in the open for everyone to see. A knot formed in my throat and tears began to form. Don’t start crying because you won’t be able to stop, I told myself. I simply could not face the extent to which I miss singing those prayers during work without completely falling apart.

I swallowed my tears and returned to my office, pretending everything was business as usual. If only I had that luxury.

Surviving Pinkwashing

All queer Jews are targeted by Israel’s "Pinkwashing”: the practice of using support for LGBTQ+ rights as a way to distract from, downplay, or justify the human rights violations they are committing against Palestinians every day. Israel paints itself as a LGBTQIA+ mecca in the Middle East, with Tel Aviv pride being one of the top pride destinations in the world.

Scene from the 2016 Tel Aviv Gay Pride Parade in which performer sexualizes and the Israeli army (Photo: coupleofmen.com)

The Birthright Trip is a free ten-day propaganda trip to Israel, Jerusalem, and the Golan Heights for young adults of Jewish heritage. Birthright has special LGBTQ+ trips and they advertise heavily to us on social media and through our temples and school hilells. These trips are designed to recruit more jews to “make Aliyah” to Israel and serves as a propaganda tour of the country. Broad City gives excellent comedic commentary on the birthright trip as simply a Jewish breeding ground disguised as a free vacation in season 3 episodes 9 and 10.

From left, Ilana Glazer, Abbi Jacobson and Seth Green in an episode of "Broad City," April 13, 2016. (Screenshot from Comedy Central) Pulled from jta.org.

Birthright’s trips for LGBTQIA+ people is known as Pinkwashing: using LGBTQIA+ rights or support for the LGBTQIA+ community as a marketing or public relations strategy to distract from unethical behavior or harmful practices. The truth is that Israel is only a safe place for LGBTIQIA+ Jews with light skin. There is a great documentary called “Escaping Silence: The Journey of Gay Palestinian Men” about Palestinian queers hiding illegally in Israel because they can’t be accepted as refugees.

The thing I find truly disgusting is that I as a Jewish American have more rights in Israel than Palestinians who were expelled from their homes and are still waiting to return. I can visit whenever I want and travel freely within the country without being harassed. I can also become a citizen any time I want, whereas Palestinians waiting to return home are forced to live in open air concentration camps.

Meeting my puzzle piece

Meeting Ru at Keshet in 2014

After college I moved back to Boston. I was incredibly shy, but I got myself over to a Keshet event—a queer Jewish organization. Slowly, Keshet events became less awkward as I met more people and recognized more people each time. As I made more contacts in the organization, I was invited to attend their fundraisers as a sponsor on behalf of Qwear. Arriving at the 2014 fundraiser, I looked around the room and hardly recognized anyone once again. The crowd that came to the fundraisers was older than the crowds at the social events, as the fundraiser had a hefty ticket price that most people my age (25) couldn’t afford. Once again, I found myself dressed in my most dapper outfit, not knowing what to do and wondering if I should have just stayed home.

And then my life changed forever. A beautiful person appeared in front of me, introduced themself as Ru, and started talking my ear off, hoping to catch my interest. The photographer immediately captured a photo of us. Amongst Ru’s babbling, I learned that they were in the midst of proving the cost-effectiveness of trans healthcare and were about to get it covered for millions of Americans and shape the future of the trans healthcare debate — shifting the focus to health outcomes and cost savings rather than religious ideologies. When I told them I had a queer fashion incubator, they nearly spilled their drink. We sat together at dinner and they drove me home. 24 hours later they were back at my house and it was clear I’d met my missing puzzle piece. Ru understood me and my gender without me having to explain myself. We became a couple instantly. Ru is now the co-owner of Qwear.

Ru’s makeshift Menorah from materials around the house

It takes time, but if you keep putting yourself out there, you will find your people. You will create a peaceful home for yourself where all your identities are celebrated within this chaotic, hateful, and confusing world. One year I forgot to order Hanukah candles and to my surprise you can’t just walk into a neighborhood pharmacy to pick them up. Ru created two custom menorahs with tealight candles from materials around the house. They are the most beautiful ones I’ve ever seen, visually highlighting the journey that is life. You fall down and you suffer but in the end, it was still worth it. The good outweighed the bad. And in many was the struggle makes the reward so much sweeter.

I try to thank the universe I’m alive every chance I get because I don’t know why I’m here, but I know that I’m given the opportunity to make a difference in the world, and that is the biggest blessing. Also, the beauty of the world just amazes me. The vast blue in the sky, the animals around us, the feeling of fresh air in my lungs. Sometimes we get so caught up in what we don’t have that we forget what we do have. We were literally designed for this Earth through years of evolution. The Earth and the universe wants us here. If you believe in God, god wants us here. Ultimately, the meaning that I find in life is through helping others through Qwear. Even though I don’t go to temple or celebrate most religious holidays anymore, I still believe I am Jewish because I follow the morals that Judaism teaches: that we are here to heal the world and build community.

Share this article

Qwear is an independent platform that empowers LGBTQIA+ individuals to explore their personal style as a pathway to greater self-confidence and self-expression.

We’re able to do this work thanks to support from our amazing community. If you love what we do, please consider joining us on Patreon!

Support Us on Patreon